Comedy is more than telling a few jokes. In this article, we’ll take a look at the various types of comedy you’ll find in film.

One thing you’ll consistently hear about comedy is that it’s hard — timing is everything, both in the pacing and in the physical action. Good comedy is gold; bad comedy is every family dinner that went on hours too long. Worse, anytime your comedy relies on finessing language, you’ve got to deal with whether or not your audience speaks the same language. Good comedy transcends language; bad comedy is insulting your host’s family tree while attempting to say something nice about the soup.

And there’s no middle ground, really. You can have a mediocre action film: the fight scene may be terribly choreographed, the explosions could look totally CGI, and the audience may notice that everyone is riding Big Wheels for your climatic road chase. But hey, we’ll still watch it.

Comedy where the timing is off? Well, we’ve all had those moments at office parties.

As much as we laud directors like Orson Welles, Alfred Hitchcock, Ingmar Bergman, and Akira Kurosawa — to name but a few — for shaping cinema as we know it, there are an equal number of writers, actors, and directors who pushed cinema into mainstream consciousness. Charlie Chaplin showed us it was okay to laugh at monsters; Buster Keaton paved the way for every fool to come later; and Lucille Ball found humor and compassion in the everyday grind of modern living.

Everything Is Funnier with a Banana Peel

The broadest sort of comedy is one that relies on physical humor. Born out of Vaudeville and stage performances, physical comedy usually relies on little to no dialogue, often has fanciful or absurd setups, and is characterized by exaggerated facial expressions and more than a little manic energy. The Three Stooges, for instance, entertained audiences for decades with a little more than a hat, a couple of fingers to the eyes, and an ear twist or two.

But this sort of comedy relies on a troupe — you need other actors to play off — and this worked well in a live setting. Film — and silent films, especially — didn’t have the same personnel requirement, but you still needed a way to perform broad physical comedy. Actors like Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin developed a style that became known as “slapstick,” in that it involved interactions with the physical environment, usually in a way that elicited howls of laughter from the audience over the perception of fantastical violence perpetrated on the actor. Pianos were dropped from great heights. People were smacked in the face with sledgehammers and frying pans. Every floor was freshly waxed, and no opportunity was passed up to get your tie caught in a revolving door.

Decades later, a young actor from the China Drama Academy would revolutionize Eastern filmmaking by introducing slapstick comedy to the martial arts genre. In fact, you could argue that the modern action film template is merely a hyperkinetic version of a Jackie Chan routine, but with more explosions and bone-breaking.

The Bettering of Strangers

Audiences reacted well to comedy, as it was an antidote to the dreariness of everyday life (not to mention a welcome distraction from all manner of economic and political upheavals). Studios, eager to keep audiences’ attention, scrambled to find other sorts of comedic material, and didn’t have to go far. There’s a long history, after all, of acerbic commentary hiding in plain sight. Shakespeare’s oeuvre, for instance, is broadly separated into three groups: the histories, the tragedies, and the comedies.

William Shakespeare was a master of writing material that was both elevated and low-brow. For every navel-gazing monologue, he had a scene of quick-tongued back-and-forth between characters whose job was to tell bawdy jokes and engage in a little nudge-and-a-wink with the cheap seats. This sort of witty repartee formed the basis of what became known as the screwball comedy — a style of film that allowed charismatic actors (both men and women) to play for laughs without having to resort to pratfalls and falling anvils.

Screwball comedies usually feature a duo, who play well against one another. Again, these sorts of routines come from Vaudeville, where a pair of actors will perform a bit that relies on a simple misunderstanding and precise timing. Unlike physical comedy, the screwball comedy works best on an audience that understands the nuances of the language being spoken by the actors (as in Abbott and Costello’s infamous “Who’s on First?” routine).

Of course, a screwball comedy has some larger plot structure to it, otherwise two hours of characters playing off each other is either a Kevin Smith film or a Steve Martin & Martin Short Netflix special. The Thin Man movies, featuring William Powell and Myra Loy, were ostensibly crime dramas, but what we remember of them is Powell and Loy bantering back and forth while knocking back martinis.

The Cunningest of Plans

Mix some physical comedy with some clever dialogue, add a pinch of wry amusement about humanity, and you’ve got yourself a parody. Parodies, in lampooning other forms of art, seek to provide commentary on preconceived notions about what is “art” and what has meaning (and why). Sometimes, they are mean-spirited, which says more about the creative than the art being parodied, but the best parodies are the ones that mock with compassion. They are love letters to the material being spoofed, but are done with the utmost respect for the source material. Christopher Guest’s entire oeuvre, for instance, everything from This is Spinal Tap (which was supposed to send up hair metal bands, but which, over time, became an indelible part of the genre) to Best in Show and Mascots.

Parodies can be tricky, however, because they require a deep knowledge of their source material. They go awry when the sentiment is “Hey, let’s make fun of this” versus “We love this so much, but come on, it’s absurd to the rest of the world.” The four seasons of the BBC’s Blackadder follow antihero Edmund Blackadder through distinct historical periods in English history, and in each, writers Rowan Atkinson, Richard Curtis, and Ben Elton plumb the literature, mores, and historical events of the time period to craft crackling dialogue that lampoons both the historical time period as well as modern cultural mores.

Laughter Is the Best Medicine

At the other end of the comedic spectrum, we have black humor, which is viewing what would normally be very dramatic and emotionally fraught topics like death, war, and murder through a comedic lens. Done correctly, this style of comedy can provide some relief from the otherwise traumatic nature of these topics. Films like Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Evan Goldberg and Seth Rogan’s This Is the End, and Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You have such an exaggerated take on their subject material (the atom bomb, the end of the world, and capitalism, respectively) that, by embracing the worldview posited by these filmmakers, audiences are able to set aside their fears. If you can laugh at monsters, they lose their power.

A comedy film isn’t limited to any one of these sub-genres. It can have elements of each style, but as a filmmaker, you have to carefully consider how each style plays within your vision. Take Only Murders in the Building, the recent streaming series by Steve Martin, Martin Short, and Selena Gomez. Broadly, it’s a parody of the cozy mystery series (right down the Arconia Building standing in for the quintessential English village). Martin and Short have a long history of playing off one another (providing the screwball comedy material), but they’re anchored to the plot by the acerbic Gomez. And naturally, there will come a point in the season where Steve Martin falls back on the physical comedy bits that have been part of his routine since The Jerk. Each episode performs a delicate dance between these three types of comedy without ever falling into one completely, which makes for a viewing that is rewarding on multiple levels.

Looking for more on film genres? Check out these articles . . .

- Think Like a Director: a Guide to the Action Genre

- Think Like a Director: Using Transitions Tell Your Story

- Think Like a Director: Creating a Foil Character

- Think Like a Director: Breaking the Fourth Wall

- Think Like a Director: How to Make a Mockumentary

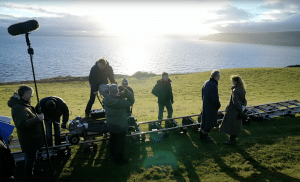

Cover image from Tim Travers & the Time Travelers Paradox (via OneTwoThree Media LLC).

Looking for filmmaking tips and tricks? Check out our YouTube channel for tutorials like this . . .