A foil character is a contrast to your protagonist that highlights their stand-out qualities. Here’s how you write one.

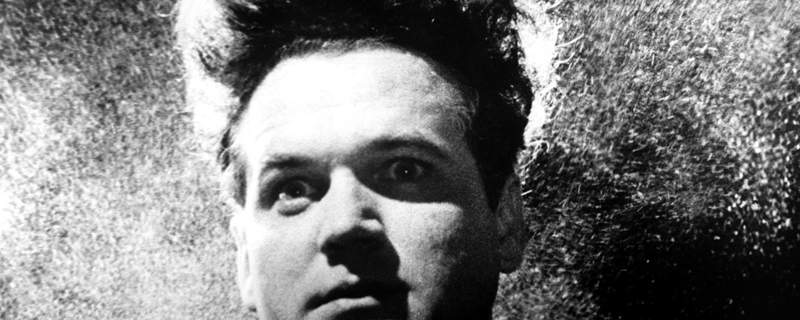

When we sketch out the shape of a story, we start with a protagonist. Well, maybe we start with an inciting event, or maybe we’re taken in by a texture of history, or even a passing mood. Regardless, you need to put a character in the frame. The audience latches on to this character, and over the course of the film, we participate in this character’s journey. Sometimes that journey is self-evident, like Richard Farnsworth‘s character in David Lynch‘s The Straight Story. Other times, that journey is less evident, like Jack Nance in David Lynch’s Eraserhead.

The Foil As Foundation

The simplest path—the route most commonly taken—is somewhere in the middle, where the character engages in a series of trials that rollercoasters them closer to their goal. Along the way, they run afoul of an antagonist, they get distracted by subplots, and they engage with a foil.

The foil is usually fourth-billing, by the way. They’re important to the story, but they’re not part of that primary triangle that forms the core of the story. The foil’s job is to reflect, enhance, and illuminate the protagonist’s story in a way that shines light on their motivations, desires, and intentions without the protagonist having to speak of these things directly.

Unless you’re Aaron Sorkin, of course, but in his case, the audience is eagerly expecting these sorts of grandstanding moments.

This example isn’t completely fair, of course, because Lt. Daniel Kaffee (played with youthful idealism by Tom Cruise) has been baiting Colonel Nathan R. Jessep (played with all sorts of fire-breathing ferocity by Jack Nicholson) for the entire film to provoke exactly this sort of outburst. The back-and-forth between these two, in fact, is a classic exercise in how foils generate narrative tension throughout a film.

The Foil as You and I

In some instances, foils are stand-ins for the audience. They are normal folk, the hard-working, stolid believers in right and wrong and how the world works. They are the voice that says “Yes, but we can’t do it that way.” They are the weight of morality that keeps the protagonist anchored, and the question of whether the protagonist sheds that burden may be a compelling element of the narrative journey of your film.

Think Steve Rogers standing up to Tony Stark in the Captain America: Civil War, the Marvel Cinematic Universe film that explored the distinction between Stark—who believes that because he’s smarter than everyone else, he can make the hard decisions—and Rogers, who believes no one gets left behind. They both want to protect humanity, but they have very different ideas of how to achieve that end. Anthony and Joe Russo, working from a script by Christopher Markus, Stephen McFeely, and Jim Simon, place the larger-than-life characters of Captain America and Iron Man (played by Chris Evans with redoubtable humility and Robert Downey, Jr. chewing on all the scenery, respectively) at loggerheads, thereby allowing the audience to understand their individual arcs (and desires and wants) without either walking around with signboards that read “Intellectual Elitist” and “Fan of the Common Man.”

The Foil as Villain

In some cases, a protagonist’s foil is the antagonist. Their philosophical or moral differences are stark enough that, even though they may appear to be of the same mind, they are, in fact, divergently different from the other. In Highlander, when Kurgan, played with tongue-wagging insouciance by Clancy Brown, tells Connor MacLeod (Christopher Lambert in a thoroughly stoic mood) that they are the same in the classic tale of feuding immortals, he’s being a bit facetious, but at the same time, he’s reminding Connor of their commonalities. They aren’t human. They don’t have the same worries and fears as everyone else. They are meant to stand apart. It’s Connor who isn’t stepping up to their intended destiny. And the audience understands that, but what keeps us involved is Connor’s efforts to be more human—to be more like us.

The Foil As Glue

Foils can be slyly mutable. Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach cleverly made Ken the antagonist, the love interest, and the sidekick in their blockbuster version of Barbie. Regardless of his place within the narrative, Ken remained a foil—the character that expanded, illuminated, and otherwise focused our understanding of Barbie. Tracking this distinction in Ken’s status within the film is a little bit like watching someone reposition a mirror around a subject. In some instances, you see an unexpected facet of a character; in others, they appear magnified or shrunken. You learn a lot about a character by how they react to their environment.

The Foil as Focus

David Mamet‘s infamous memo to the writing room of The Unit points out that audiences want drama. If they want information, they’ll tune in for newscasts. Their recreational TV needs to, well, recreate, and the basic formula for providing that is to build each scene as a struggle between what one character wants and why they can’t have that. This struggle can be illuminated by the exploitation of your foils.

We’re in the storytelling business, after all. We’re not documentarians. We want to make our audiences feel something. We want them to see themselves in our characters, to understand themselves better through our narrative. We have to show them the way; we can’t tell them. Using foils is misdirection, a bit of stage magic with mirrors, but that’s part of the illusion, isn’t it?

(Cover image courtesy of Warner Bros.)

Looking for filmmaking tips and tricks? Check out our YouTube channel for tutorials like this . . .