One of the often-overlooked ways that a director can manipulate the narrative is the transition. Let’s explore how they can affect your story.

There are a lot of fancy names for transitioning from one scene to the next: the fade, the swipe, the dissolve, the jump cut. Each of these transitions contribute to the pacing and subtext of a scene. The jump cut, for instance, is used to fast-forward the progress of a scene.

Traditional filmmaking attempts to create an immersive and seamless world in which the audience can be submerged, dipped deeply enough that they forget they are watching a film. Of course, accomplishing this would mean the director has to film a series of continuous shots. Sam Mendes made us all believe this was possible in 1917, (with a nod to the incredible cinematography by Roger Deakins), but it’s almost as artificial a construct as using a multicam setup for dramatic TV. Switching POVs during a scene certainly makes it easier for the audience to witness each character’s actions and reactions, but if we were actually in the room, we wouldn’t be racing from spot to spot to witness the scene.

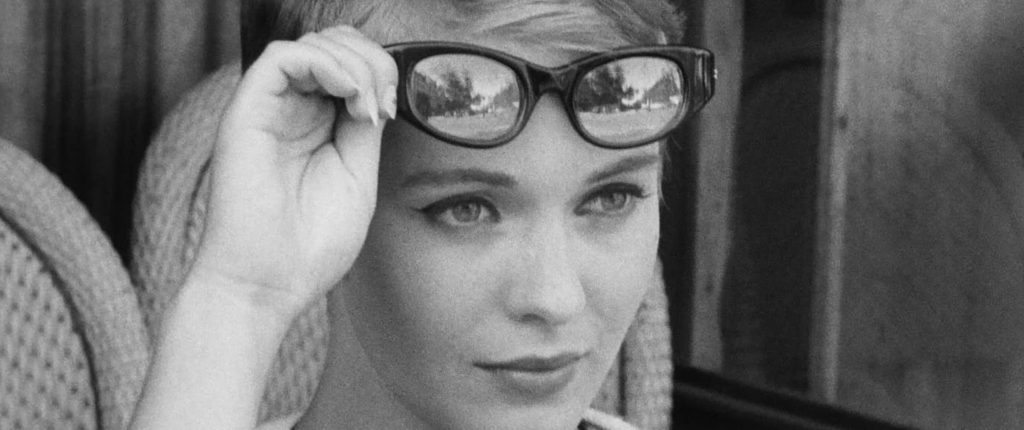

If the audience can sustain belief with a mulitcam POV setup, they can probably handle jumping over the boring parts of a scene in order to maintain the narrative direction. It was Jean-Luc Godard with Breathless in 1960 who started playing with jumping forward even farther in these transitions.

Jumping Jacks

Each of these individual transitions was a distinct cut — a demonstrative “we’re done here; move on” ending. They were not a gentle dissolve or a wipe or a fade out and a fade back in. They were sharp and distinct. This scene. This scene. This scene. What sustains the audience throughout is the narrative being shown. Two actors get in a car. Cut. The same actors getting out of a car in a different location. We know we missed the driving from location A to location B. We also don’t care, because the director has told us “we’re done here; move on.”

While the jump cut allows us to shorten time and collapse the narrative to key moments, it is jarring when it is used to jump between storylines. Let us revisit the couple in the car above. They get in the car. Cut. We’re watching an entirely different couple look out the window of an airplane that is sailing above the clouds. Every member of the audience is now wondering if they’re in a different film entirely. Our brains can’t follow how we got from car to airplane.

For the most part, however, we are merely transitioning from one scene to another. The dissolve is our friend. Making a more leisurely transition from the first scene to the next allows the audience to keep up with this shift in the narrative. “Oh, we’re done with the car scene; now we’re watching a new scene, and there’s an airplane in it.” We can park storyline A (the kids in the car) off to the side, while we deal with storyline B.

There are a variety of ways to do this dissolve, of course. There’s the slow crossfade, where one scene dissolves into some aspect of the next, signifying that some aspect of the prior scene is informing the next, even if that new scene is distinct and separate. There’s the “camera drifts through darkness on its way to the next scene” dissolve, which, again, maintains some connective tissue between the last scene and the next, but which still signifies a new scene.

Wipe-Out!

But the simplest transition is the wipe. The wipe handily implies that we’re not done with the narrative line we just left. Whatever is happening there is merely pushed aside for awhile, while we attend to another part of the story which is likely happening concurrently. You’ll see these often in films that have multiple storylines that are running on some kind of dramatic countdown. The Star Wars Saga used them extensively, as we regularly hopped across light years to track all the narrative action in the course of the film.

Speaking of hopping across light years, the fifty seconds of “lightspeed skipping” in The Rise of Skywalker is neither a jump cut nor a dissolve. It’s a sequence of ordered cuts followed by flashes to white. Even though the real-world science is really dodgy (I know: it’s a little late in the game to be fussy about science in Part NINE of the Star Wars Saga), the filmmaking is precise and controlled. J. J. Abrams lines up an ordered sequence of shots — establishing location, character reactions, more character reactions, location again, transition — and makes it all work. Why? Because each “skip” is a fade to white, and each cut within the sequences maintains the narrative through-line.

The Whiter Shade of Pale

And what is the fade to white? “Fade to White” (as well as the more traditional “Fade to Black”) is a signal to the audience that we have reached the end of a scene. A fade to black typically indicates a conclusion—some sort of ending — but the fade to white suggests there is something as yet unresolved. Has the narrative been left open? Are we supposed to reach our own conclusions about what we’ve just seen? Or is it merely a subtle nudge that while one story is ending, another is beginning. Think of it as an inhalation instead of an exhalation.

Over the course of seven seasons, The West Wing used a FADE TO WHITE twice. Once, at the end of the penultimate episode of the second season, to suggest to us that everything was still in question. We didn’t know what had just happened. All we could do was sit on the edges of the couch for a week to let that breath out.

The second time was at the end of Season 7’s episode featuring the marriage of Ellie Bartlet (gracefully portrayed by Nina Siemaszko). In this instance, the FADE TO WHITE is both an ending and a beginning. Characters are transitioning from one state to another. When we exhale — when we come back to this story — things will be different. Characters will be gone. Life will have moved on.

Back in Black

Which brings us to the classic transition—the FADE TO BLACK. This transition is an exit. The story disappears from the screen. We are left with nothing. Our brains think “Okay, this thing is done.” We exhale. We are transitioning to something else.

Even if the next scene involves the exact same characters in exactly the same location, we will instinctively think that time has passed. If we see two people getting into a car, followed by a FADE TO BLACK, and then a return to the couple in the car, our first thoughts are going to be: How long have they been sitting in that car?

As you edit your project, keep these transitions in mind. There’s a lot of subtle messaging you can deliver to your audience as you move into and out of scenes. Use these transitions to extend and amplify your narrative. Don’t leave them wondering what they missed.

Cover image from Twin Peaks, courtesy of Showtime.

Looking for filmmaking tips and tricks? Check out our YouTube channel for tutorials like this . . .