Retrofuturism is the design trend that is always on the cusp of arriving but is never out of date. Here the key elements of retro-futurism.

It’s always been difficult to pin down exactly when the future is going to arrive, and many forward-thinking writers have said that it’s already here. Without getting into too much hand-waving and long-winded arguments about syntax, let’s say that both of those positions are correct.

The “future” is a dream of the present, but next week, that dream will be the past. We’re always arriving at the future, and it might not have the flying cars and jet packs we imagined it would, but it does have watch phones, nearly instantaneous data transfer, and virtual reality goggles. Most predictions of the future are going to wind up being curiosities of history.

Should we bother making predictions? Of course we should. It’s in our nature to imagine what might happen next, and science fiction builds a blueprint for how creativity and technology can reach this future— even if that future is always a day or two away. We’re still waiting for our personal jet packs, right?

Let’s take a look at how the retrofuturism sub-genre operates.

The Future Takes Root in the Past

In order to imagine the future, we have to look at the past — at what has been done, at what failed, and what seemed really goofy at the time, but oh, boy! we can totally fabricate slabs of unbreakable glass now, can’t we? It was H. G. Wells, in his 1898 classic The War of the Worlds, who looked up at the heavens and wondered what sort of life there might be on Mars. Of course, in his dystopian vision of the future, the inhabitants of Mars came here with their three-legged, cyclopean machines and melted down half of London. The only thing that stopped them was a common virus to which humanity had developed an immunity.

Jules Verne, in 1870, imagined traveling for thousand of leagues under the sea without needing to surface for air. His vision of undersea life led to the development of the submarine, deep-sea submersibles, and (frankly) James Cameron‘s career. So, yes, because of Captain Nemo, we have Avatar: The Way of Water.

Even Mary Shelley, while writing a ghost story in 1818, imagined restoring life to dead tissue. Sure, she used alchemy and lightning to power her science, but that didn’t stop generations of scientists from trying to figure out how to sequence DNA and grow human ears on rats.

Each of these authors imagined the future, and even though the facts of their futures were implausible, the dreams were real, and we’ve been chasing those dreams ever since.

Retrofuturism film projects, like the sub-genre itself, must imagine the future cinematically, not just in theory. Here are a few futuristic royalty-free clips to get you started.

- Neon Sci Fi Futuristic Alien Spaceship Modern Vibrant Purple Blue

- Animated 3D Digital Smart City Walking Motion Graphic

- Motion stars and planets in galaxy

The Future as the Road Not Taken

This leads to the key distinction between retrofuturism and traditional science fiction futurism. Retrofuturism takes a key futuristic element and spins a world out from the discovery of that element. Traditional futurism imagines a future and extrapolates how we get there. It is the difference between Star Wars and Star Trek, if you will. It is the difference between nostalgia and hopefulness.

Star Wars tells us up front: “A long time ago, in a galaxy far far away.” This isn’t the future; this is history. This is the way the world was, once upon a time, and this evokes nostalgia — a fond remembrance that evokes warmth and security (even as the Empire tries — again and again — to obliterate entire star systems).

We spend an inordinate amount of time in locations that are undeveloped, in ruins, or are otherwise in disrepair. There are worlds that have fallen apart, even with flying cars and laser swords and space-faring taxi cabs. The world is cobbled together from spare parts, detritus, and wreckage from prior civilizations. Star Wars is perpetually the frontier, where everything is held together with one rusty nail.

In contrast, Star Trek is shiny, smooth, and filled with virtual screens that broadcast more data than the human eye can handle. We don’t understand how this future works, but there are parts of it that we want to emulate. This future is the dream we aspire to. We used to marvel at the slick data pads used by the crew of the Enterprise in Star Trek: Next Generation, and now, they’re nearly ubiquitous in the hands of our children.

Retrofuturism films need the busted, broken, and ruined edifices of the past. Here are a few retrofuturistic clips you could use in your next project.

- Graffiti on a ruined building

- Derelict Industrial Buildings Long Island

- Exterior establishing shot of abandoned buildings in the Namib desert

The Punk Aesthetic

Retrofuturism is the punk rock aesthetic of the shiny future’s sold-out arena rock show. It is the grungy underbelly, the perpetual DIY attitude that gets us from the failed infrastructure of the present to the slightly less dystopian future. It has more zippers, clamps, binders, buckles, and extra tape than the fancy future. It gets things done with what is lying around. Retrofuturism is built upon the junk of the past. If you have a flying car, then it is definitely a rebuilt cherry red 1933 Ford Coupe with jet engines bolted on to the back.

The art of Jean Giraud, a.k.a. Moebius, is the dusty dystopia of retrofuturism. His worlds are filled with sand-blasted blocks of forgotten civilizations and vast landscapes bubbling over with the shattered remnants of giant organic growths. People wear outfits that freely mix desert nomad couture and plasticine haz-mat attire. They fly about on albino pelicans. It’s equally fantastic and futuristic, and his color palette is suffused with nostalgic watercolors.

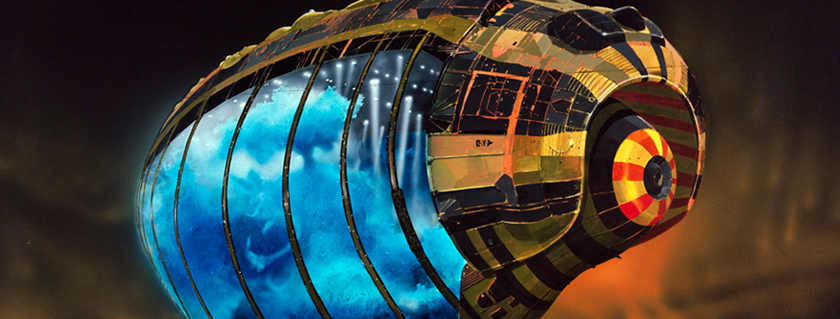

Chris Foss, on the other hand, builds his retrofuturism with geometric lines and vivid colors. His spaceships are as aerodynamically improbable as they are visually pleasing. Whereas Moebius’s future feels lived in, Foss’s future looks much more like the sort of attire you’d see on a runway model — you don’t quite see the functional use of it, but you know you’d look cool wearing it.

Bokeh effects are a great way to evoke a dreamy, retrospective vibe. Here are a few of our favorites you could drop into your own retrofuturistic sequence.

- Swirling Snowfall Against Black Background

- Car Lights Out of Focus in New York

- A Shimmering Celebration Of Red Bokeh Lights (Loop)

It’s Hip to Be Square

It can be difficult to imagine the future, much less how we get there. Retrofuturism in film looks to the images and aesthetics of the past to craft something future-adjacent. It’s an imaginary world, filled with familiar icons and images. It’s nostalgic — which, as we know, creates a sense of well-being and comfort—without being kitschy. Using the key elements of retrofuturism—those faded designs, those familiar shapes, the graphic lines and outlines — you can craft a future that looks inviting. Intuitively, we understand how to navigate the retrofuture world, and that makes it seem like someplace we’d like to visit.

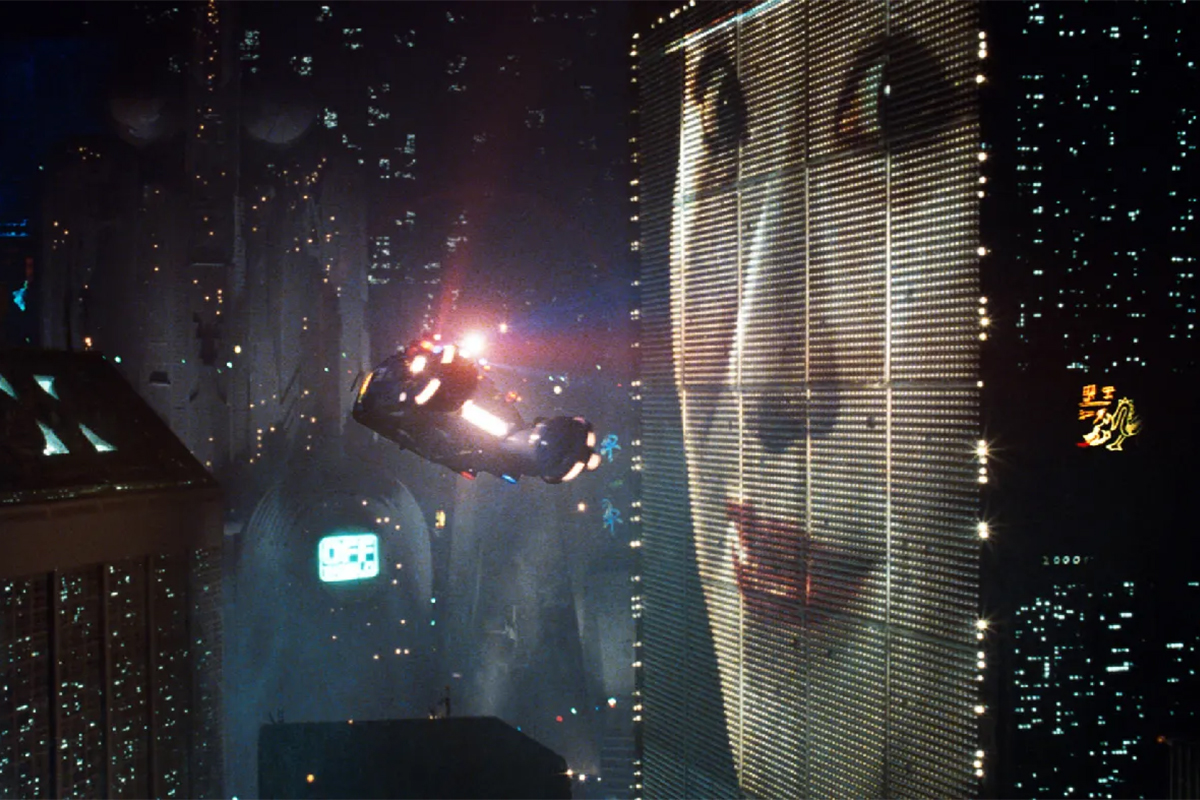

Cover image via Blade Runner (Warner Bros.).

If you’re looking for tips and tricks to improve your filmmaking, check out our YouTube channel . . .

Looking for more articles on the filmmaking industry? Check these out.