Jordan Peele’s horror films are one-of-a-kind, and “Nope” is no different. Let’s break down what makes this film so successful.

One of my favorite pastimes is going to see a Jordan Peele movie. While I’m not alone in this, there’s just no denying the horror director’s films are a breath of fresh air. There’s a guaranteed sense of excitement that comes with seeing his unique stories play out on the big screen. Even if you’re not a big horror fan, there’s no denying his films are theatrical experiences worth having.

His latest film, Nope, once again breaks new ground on what horror can be — and what it means to be entertained at the cinema. Through a meticulous choice for the principal camera and VFX work, Peele’s film has earned the interest of filmmakers and enthusiasts for years to come.

So, here are three ways Nope’s cinematography and direction truly broke new ground.

Capturing the Sky

Peele has talked extensively in recent interviews about his insistence on the film’s necessity to portray the idea of spectacle. The two main characters (and three secondary characters) are meant to feel small. This smallness adds to the dread and tension that comes with each developing plot point, and Peele knew that. One of the central themes of the film deals with our inability to look away from horrific images — specifically, looking toward the sky.

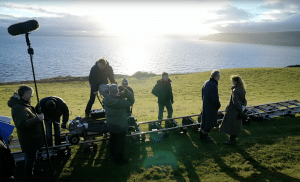

To start this process of creating visually striking images, Peele enlisted the help of cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema who decided to use IMAX 65mm cameras to bring the spectacle. So we’re talking big negatives in a big camera, producing big images. What do those images look like exactly? What does any of this actually bring to the table? The film is 65mm wide, which is almost twice the size of a normal frame of 35mm film. Overall, the images have a bigger look and feel than something like 35mm — or something from a digital sensor.

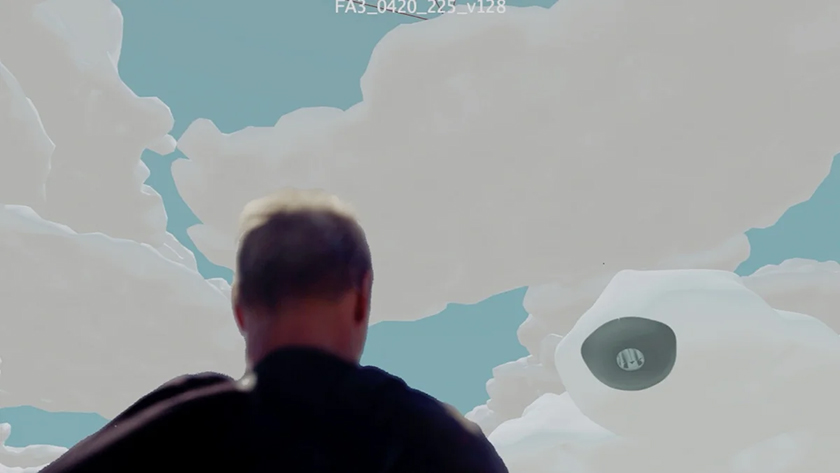

Another part of creating that spectacle fell to VFX supervisor Guillaume Rocheron, who had to create a digital sky for almost every single shot that includes the sky . . . let that sink in for a minute. Given the importance of the clouds in the sky, and the number of scenes that take place outside, the look had to be just right for certain sequences to work. This was such a vital aspect to the film that Peele enlisted the help of Rocheron in pre-production to determine just what Jean Jacket would look like and how to design certain set pieces.

While it isn’t uncommon for big-budget films to enlist VFX supervisors early on, Rocheron’s input was integral to writing certain elements of the story. This is just one of many ways a film like Nope could only work coming from someone like Peele. This understanding of how to bring a team together under a unified vision for the story is rare for modern filmmakers.

Shooting Day for Night

One of the key plot aspects of the story is that most of the action takes place at night. Specifically, the action takes place in a big field with no lights in the mise en scene. Naturally, this raises the question, How do you shoot this? If you’ve seen the film, you know the look of these scenes is pretty surreal — at the time, I didn’t quite know what I was looking at or how they shot it. Since the film’s initial release, the production team has revealed just how they pulled off these night exteriors.

Hoyte designed a rig that housed a Panavision 65 (film camera) and an Alexa 65 (modded infrared digital camera) positioned below the film camera pointed up toward the line of sight from the film camera, at a mirror — so the two images would be positioned and aligned in the exact same point of view. Then Hoyte would overlay the two images in post-production. This probably sounds confusing, but Hoyte did something similar to this before on Ad Astra. I’ll let Hoyte explain it best with a quote from his interview with Kodak:

We purchased two decommissioned 3D-stereo camera rigs on which we could mount two cameras. One was an ARRI Alexa, specially customized to capture infrared, the other a regular 35mm film camera. Instead of lining-up the cameras for 3D parallax, we found a new way to align them so that both cameras were shooting the exact same image – one infrared, the other on film – so that every frame would overlay perfectly later in postproduction.

For Nope, Hoyte knew he had to scale everything up to bring the spectacle that Peele wanted. But doing this presented some challenges in the form of lenses and actually building the rig to accommodate large-format cameras. Hoytema goes on to explain:

In the early stages, we took a rather shabby-looking prototype rig, held together with screws, cable ties and gaffer tape, out into the desert to shoot tests. My DIT, Elhanan Matos, is not your standard DIT, and when we do new technology like this, he’s all over it. He helped in getting the two-camera synched up, and although the video taps on the 65mm camera remain poor, he gave us a good on-set approximation of what the final image would look like. We then liaised with my DI colorist Greig Fisher at Company3 in LA, mixing those two sets of images together, and the result looked to me like an entirely plausible-looking night. In fact, using this technique you can peer much deeper into the dark expanse than we had done before on Ad Astra. And, after additional lighting effects were added in VFX, our night scenes really came alive.

For these scenes, and the other daytime and magic-hour scenes, Hoytema shot on the Kodak VISION3 250D stock; he chose the 500T stock for nighttime interiors. Hoytema is my personal favorite DP working today, and I can’t wait to see what magic he’s cooked up next summer for Christopher Nolan’s next film Oppenheimer, which Hoyte shot on large-format IMAX black-and-white film stock, which is another groundbreaking feat of cinematography.

Using Miniatures with IMAX Cameras

This might be a less-groundbreaking detail, but one of the most shocking and memorable scenes in recent memory takes place about halfway through the film. I’m not going to spoil anything, but we finally get a sense of what’s been happening through a quick, less-than-sixty-second shot. The camera was turned on its side, LED lights were used around and behind the miniature to add color and texture, and then certain elements were then added in post-production to bring it all to life. It’s old-school-innovation at its finest, and the result is one of the most disturbing, memorable scenes I’ve watched in long time.

In my opinion, what makes this so innovative is the fact that they used a miniature and shot it with large format IMAX film cameras . . . that doesn’t happen anymore! Not only does this add to the realism of the scene, but in my opinion, this feels like Peele and Hoyte following the ethos of the film itself during its production. Peele has said in interviews that he asked Hoytema how he would film a UFO if he had too in real life. He asked him what cameras would we use and why. Hoytema responded with “IMAX film cameras.”

Everything in the film ends up feeling like one, carefully crafted, purposeful decision after another. The final product is the result of brilliant filmmaking and collaboration, and filmmakers everywhere could learn a thing or two from studying this masterwork.

Cover Image via Universal Pictures.

Looking for some music for your projects? At Videvo, our library has everything from free ambient music to music for streams — perfect for any indie project:

- Royalty-free Christmas music

- Royalty-free meditation music

- Royalty-free upbeat music

- Royalty-free jazz music

- Royalty-free Halloween music

Need a break? Check out our videvoscapes — the ultimate reels for relaxation or concentration. Each videvoscape collects hours of high-definition nature footage and background video with downtempo chill beats for the ultimate escape from the grind.