Forced perspective is a classic technique that can bring some innovation to your low-budget project.

One of the first discussions in any sort of art class is about perspective, which is the relation of the viewer to the image being presented. It was Leon Battista Alberti, a Renaissance humanist, who put some math behind his argument that artists should replicate nature as realistically as possible. De Pictura, his classic treatise on the relevance of optics and geometry, laid out the principles of perspectivity, demonstrating how to create depth and authenticity of a three-dimensional image in a two-dimensional medium. The TL;DR version is that, in relation to other objects of a similar nature, smaller things are farther away.

Part of what Alberti talks about in his geometry discussion is the importance of the z-axis, which is the invisible line that extends from the viewer to the most distant object within the image. If all objects are ostensibly of one size (say, “monster”-sized, as in the classic Sesame Street video above), then we will intuit that the smaller objects are farther away. As you can see in the video, these monsters are, in fact, all the same size, and as they traverse the z-axis, they get bigger as they get closer.

Of course, to pull this off as a filmmaker, you need a large depth of field. A wide-angle lens will allow you enough room to play with the staggered spacing of objects, making them appear larger (nearer) or smaller (farther away) as necessary.

The simplest use of forced perspectives is to make objects appear larger than they really are. Throughout The Lord of the Rings, for example, Peter Jackson often had to rely on tricking the audience so as to make Gandalf appear much larger than his hobbit companions, especially when the Fellowship was outside, where it’s much more time-consuming and costly to green screen everything. Of course, to maintain the illusion the actors have to maintain eye-lines in accordance with this z-axis dance, and this is where we get back to Alberti’s discussion of geometry from five hundred years ago.

A split rig is a set-up where objects within the frame (which is being filmed with a wide-angle lens, remember?) are arranged in order to facilitate the illusion you want to sell. Objects closer to the camera are physically smaller than identical objects farther way. When you put an actor next to the closer objects, they will appear larger than the other actor farther back in the frame. Why? Because of the other referential objects in the frame. If the foreground actor picks up an orange (which is actually one of those tiny satsumas) and their hand dwarfs it, then the actor in the background picking up an actual orange will appear smaller to us because our brains are going to try to formulate a connection between those two similar-looking orange shapes.

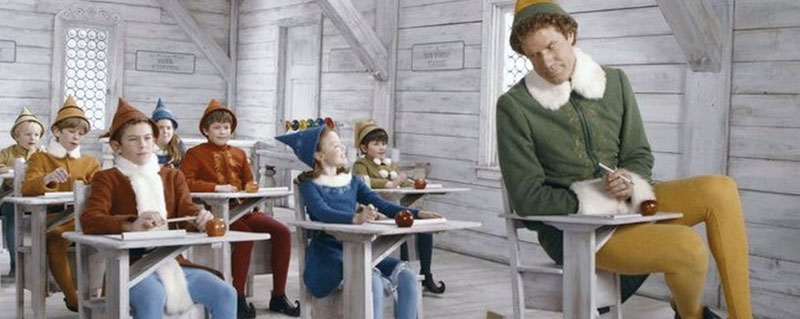

And sometimes the easiest trick is to build everything at a slightly different ratio in order to make some characters appear larger than the rest. Build your sets at three-quarter size, put your lead in the foreground, and suddenly, you’ve got a giant walking around the workshop, as Jon Favreau did with Will Ferrell in Elf. Not only a classic holiday day, but Elf is also a master class at using props and perspective to create the illusion that Ferrell’s character is much bigger than everyone else around him.

Michel Gondry uses this technique to disorient the audience in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. As Joel struggles to hold on to his memories of Clementine, he falls into a nightmarish recreation of a childhood memory where he is trapped in the family kitchen by a giant version of Clementine. Gondry is using a visual technique known as the Ames Window to make Joel (played with childlike panic by Jim Carrey) appear much smaller. The room is trapezoidal, but appears rectangular and deep, as objects at the “back” seem tiny in comparison to objects closer to the front. Of course, the illusion is facilitated by other objects in the room being larger (or smaller) than they should be in order to force our perspective.

Forced perspective is one of the simplest special effects you can pull off. All you need is a tape measure and a little math, and you, too, can film Gulliver’s Travels to Lilliputia in your own back yard.

(cover image from Gulliver’s Travels, courtesy of Twentieth-Century Fox)

Looking for filmmaking tips and tricks? Check out our YouTube channel for tutorials like this . . .